Mary Wears Her Scars Like the Rest of Us

Last week, my Women and Religion students studied Pomba Gira, an Afro-Brazilian deity worshipped by women in the favelas of Brazil. Pomba Gira is a scandalous icon for the devout Catholic. She's often depicted in low-cut dresses that showcase her cleavage; sometimes, she’s fully topless, a red or black cape draped over her shoulders and bikini bottoms. Her skimpy outfits, always paired with red lipstick, lead outsiders to label her a femme fatale, a harlot.

It’s more than her appearance that links Pomba Gira to women’s sexuality and all that comes with it—depravity, immorality, danger, even the occult. Located on the margins of Brazilian cities, the overcrowded, underfunded favelas are notorious for their high poverty and crime rates; drug trafficking and sex work are prevalent. Within the favelas, women are both the breadwinners and caretakers of their multigenerational households; they earn a living, feed their families, and care for the elderly. Men are, more often than not, a nuisance.

Pomba Gira provides the cure for those nuisances. Followers offer her candles, roses, and perfumes; they may even light a cigarette or two and place it before her statue. Women further show their devotion by purchasing perfumes, soaps, and oils bearing the deity’s likeness, which, with her olive-to-bronze skin tone and wavy black hair, is similar to theirs. This relationship is mutual: If they take care of themselves, then Pomba Gira will take care of them, too.

It might be appalling to write about Pomba Gira on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception. As I told my students, Pomba Gira appears to be the anti-Mary, the icon for sex workers, single women making a living for themselves and everyone else, scorned women dealing with their cheating or deadbeat husbands, and women whom the government and the Catholic Church in Brazil have abandoned. Still, after my class, I sat in my office reflecting on Pomba Gira, her devotees, and the Virgin Mary.

Who do Catholic women like myself—single, childfree, wage-earning, caretaking—turn to?

Every Advent, I brace myself for the flurry of sermons and articles about Mary. Even though, a long time ago, I “played” the Virgin Mary in my parish’s Stations of the Cross, I’ve never felt truly connected to Mary—or, at least, to those traditional images of Mary that my students analyzed in relation to Pomba Gira. Nearly every image we found online portrayed a closed-lipped, lily-white Mary veiled in blue, her hands clasped in prayer. Meanwhile, Pomba Gira always presents a "power stance," her feet planted firmly and her head held high.

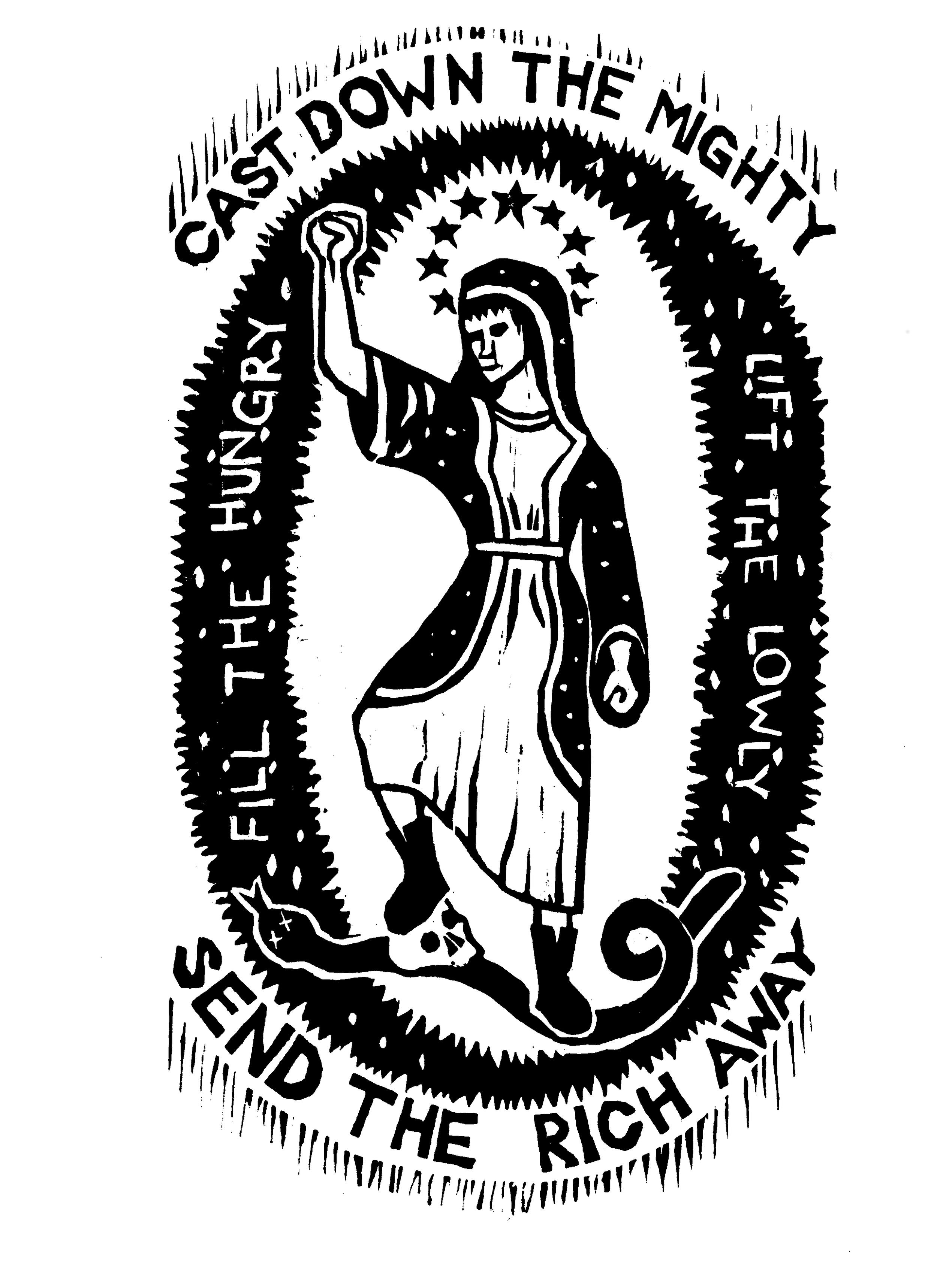

Ben Wildflower’s illustration of The Magnificat.

We know Mary had power, relayed so vividly in The Magnificat. In recent years, Christian artists such as Ben Wildflower have taken lines from The Magnificat, specifically the verse “cast down the mighty from their thrones,” and reimagined Mary as a liberator—not only through her gestation and ensuing birth of Jesus but also through her own cultivated ability and hard-earned resilience. And, as the Magnificat reminds us, Mary was a “lowly servant,” an unmarried, working-class girl who at first doubted the Angel Gabriel’s plan.

As more Catholics come out as pro-choice, the slogan “Mary had a choice” has grown popular in both Catholic and reproductive justice circles. While it’s true that Mary did consent to Gabriel, I now read that conversation between Mary and Gabriel as one of incredulity and vulnerability, perhaps even a reveal of low self-worth, rather than a girl enacting modern-day notions of choice. Mary was in no place to challenge authority; she enacted agency, but her options were limited. The Angel Gabriel provided her with a way forward.

Consent and agency were the leading themes of my Women and Religion course. This wasn’t by design; as the course unfolded, we realized that so many practices and rituals related to women and gender-marginalized bodies challenged our Western notions of consent and agency. Too often, we reduce these concepts to autonomy and individual freedom without ever questioning what that may look like for women and gender-marginalized folks or different ethnic groups and cultures across varying historical and sociopolitical contexts. My students acknowledged how many religious rituals and icons formed at the intersections of consent and violence, agency and oppression. Practices that may have initially alarmed us, such as Pomba Gira devotion, become understandable resources for women and gender-marginalized people needing strength and self-care to survive in a world they didn’t choose or create.

Icon of Our Lady of Częstochowa.

Last Advent, I facilitated a Zoom session on the images and apparitions of Mary with my Nuns and Nones NYC community. I presented the images that I’ve been drawn to over the years—the ones that compelled me to rethink Mary, the Virgin. Our Lady of Częstochowa, the Black Madonna, bears permanent scars on her right cheek. (I’m of Polish heritage, and the tale of the Black Madonna has become inextricable from Polish identity.) Our Lady of La Vang, a lesser-known apparition who, in 1798, appeared to persecuted Vietnamese Catholics praying the rosary in a rainforest and whose image and devotion were recreated centuries later among Vietnamese-American communities in California.

The sisters brought their own unconventional versions of Mary that I will never forget. One sister shared an image of Mary as a breast cancer patient, her bald head wrapped in a pink scarf. Another shared a photo of Mary as a widow. “We never talk about Mary after Jesus’ death,” this sister said, “but Mary’s life continued.”

We’re not accustomed to thinking about Mary in this way. We're still stuck between two poles, Mary the Meek and Mary the Mighty. Yet even these new depictions of Mary the Mighty don’t acknowledge her full humanity as a woman dealing with the many nuisances of living or the aches of loneliness, singledom, widowhood, illness, and old age.

Mary is our resource, and she wears those scars like the rest of us.

Lauren Barbato is the executive director of Call To Action.